Changing chocolate

Project created by: Dr Natalie Fey and Dr Ben Mills

The NFWI has teamed up with the University of Bristol to create a series of worksheets for you to try with your WI. This month is a taste test involving plenty of chocolate...

What’s involved?

Melting chocolate, then letting it solidify again at different temperatures and tasting the results.

You will need:

- 3 pieces of chocolate (milk or dark) – if you are doing this with friends, 2 bars of chocolate of the same type

- A source of heat to melt the chocolate – this can just involve warming the chocolate bars on a radiator until they have become soft (careful, you don’t want leaks), but you could also melt the chocolate in a microwave or on a water bath. Here we are going to use the microwave and work with smaller amounts of chocolate.

- A freezer to cool the chocolate

- 3 plates and a spoon

Safety

This is an activity that you might encounter as part of making a dessert, so there are no chemical risks. Sadly, eating too much chocolate involves a certain amount of risk (even if it’s in the name of science!), but this is a safety issue most of us have some experience of.

Procedure

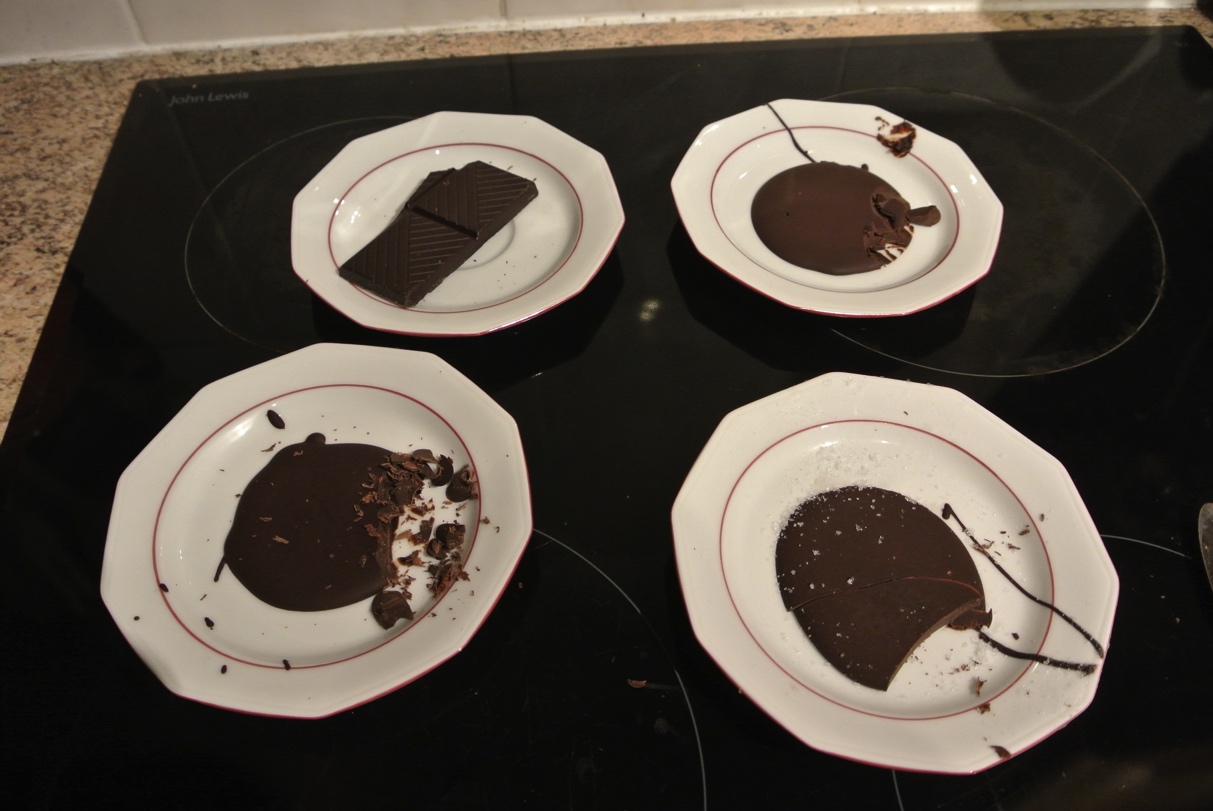

- Step 1: Put 1 piece of chocolate aside for later. Heat the other 2 pieces in the same bowl until the chocolate melts. If you are using the microwave, break off small pieces of chocolate (1-2 rows from a bar) and place in a bowl or mug suitable for microwave use. Then heat this on high in short bursts (20-30 seconds), decreasing the time as the chocolate becomes soft. Stir between heating. (If you are preparing for a large group, set aside 1 chocolate bar and soften the other by putting it in a warm spot, e.g. on a radiator.)

- Step 2: Stir the chocolate until all of it has molten. Then divide this between 2 plates. (No need for this with chocolate bars.)

- Step 3: Place 1 plate in the freezer and leave the other out in the kitchen, covering it (without sticking to the chocolate) if there are flying insects or greedy partners/housemates about. (Or just put the softened chocolate in the freezer.)

- Step 4: Now wait until the chocolate at room temperature has set. Take the plate out of the freezer and see if the 2 samples look different from each other; also compare them with the piece of chocolate you saved at the beginning. Now break off a small piece from each and taste it. The frozen chocolate is likely to be cold and brittle, but can you detect differences in creaminess once they melt in your mouth?

- Step 5: Let the freezer sample warm up to room temperature (again, with a cover if needed). Now compare the taste of your 3 samples again. (Or just 2 samples if you are working with chocolate bars for a large group.)

- Step 6: Appropriately dispose of any leftover chocolate and clean up after yourself.

Brief explanation

Chocolate contains cacao butter a main ingredients. Learn more in this blog post.

The fats in cacao butter have at least 6 different forms in the solid state, which are also called polymorphs. The different arrangements can lead to different properties in the chocolate such as melting point, how easily it snaps, strength, glossiness and texture. It is therefore important that manufacturers deliver a product with the correct polymorph to the consumer. The polymorphism of cacao butter is still an active area of research.

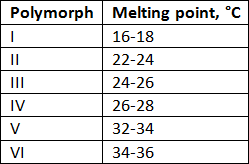

The polymorphs can be classified and distinguished by their melting points, as shown in the following table:

Polymorphs I – IV are not suitable for making chocolate because they are unstable at room temperature (18-25 °C, depending on where you are). Polymorph VI is the most stable, but has been found to taste bland and be too brittle. Polymorph V has been found to have a far superior taste, texture and appearance compared to the others. This form has a shiny appearance, produces an audible snap when broken, melts in the mouth, and has a smooth texture, which ticks all the characteristics required by any chocolate connoisseur. However, polymorph V is not the most stable of the 6. Form V can convert to form VI over the course of several months. The chocolate becomes harder and melts too slowly in the mouth due to the higher melting point.

In this experiment, the chocolate sample allowed to solidify at room temperature likely contains a mixture of polymorphs I-V, dominated by forms IV and V (IV is accessed by solidifying at 16-20 °C and V requires stirring). It will melt quite easily but be closer in behaviour to the shop-bought sample. It could be converted to a better sample of mostly polymorph V by a process called ‘tempering’, where it is re-heated carefully to just below the melting point of polymorph V, melting the other polymorphs. When solidifying again (often with light stirring), the fats will be templated by the polymorph V crystals, making this the main form.

The chocolate cooled in the freezer is likely to have a larger proportion of forms II and III – polymorph II is accessed by cooling at 2 °C and polymorph III at 5-10 °C. It has a sharp snap while still mostly frozen, but then melts very easily in the mouth. This sample is also likely to be very sticky when allowed to warm up to room temperature again.

This demonstrates why chocolate work is such a delicate and skilled process.

Possible extension

If you have a good kitchen thermometer and are prepared to set up a water bath, it is possible to measure the melting points of chocolate samples prepared by the different methods described above, giving better insight into which polymorphs are likely to be present.

For this, you take a few small pieces of chocolate prepared by a procedure and place it in a suitable bowl on a water bath. You then time how long it takes to melt, and also measure the temperature at which the sample melts. This allows a more quantitative comparison of the effects of different preparation methods on chocolate properties.

Find more details and a full procedure on the RSC Learn Chemistry website.