Cabbage indicators

Project created by: Dr Natalie Fey and Dr Ben Mills

The NFWI has teamed up with the University of Bristol to create a series of worksheets for you to try with your WI. Love it or loathe it, cabbage is a key component to test acidity in this month's experiment...

What’s involved?

Acids and bases can be found in the home and the garden, and their strength can be measured by boiling cabbage leaves in water, pouring off the liquid and using it as an indicator solution.

You will need:

- A red cabbage

- A glass measuring jug

- A kettle (or pan) to boil water

- Some small cups or glasses – shot glasses and disposable white plastic cups work well

- A suitable work surface (e.g. stainless steel sink, marble worktop, glass surface protector or glass cooker hob)

- Household products whose acidity or basicity you want to test, such as: vinegar, cola, red wine, liquid soap, lemon juice, laundry detergent, white wine, bicarbonate of soda

Tip: you only need a small amount of each product to test, a few drops or a teaspoon’s worth.

Safety

You will only use things you are likely to find around the house already or can buy without restrictions, but here are a few tips to help avoid any problems.

Boiling water is likely to be the worst of your troubles in this experiment. Just be sensible, really.

Red cabbage has a habit of staining skin, so having a sink nearby to wash your hands can be helpful. Alternatively, wear gloves, especially when breaking it up to make the cabbage indicator.

If you mix lemon juice or vinegar with bicarbonate of soda at any point, be prepared for the mixture to bubble up and escape its container. If there’s cabbage indicator in the mix, you might stain your work surface, depending on what it’s made from.

Many household products have safety information on the packaging. Please take note of this information before you use a product in this experiment. You may want to wear gloves, eye protection and an apron.

Workspace and activity

As well as your skin, red cabbage can stain fabrics, so work on a metal, glass, plastic or granite surface and perhaps don an apron. Keep away from unvarnished wood and carpets, too! The kitchen or utility room is your best bet for this experiment. Keep an old cloth or a kitchen roll to hand to wipe up any spillages.

Procedure

Step 1: Tear a few leaves off your red cabbage and put them in a measuring jug.

Step 2: Boil about 200 ml (⅓ pint) of water and pour it onto the cabbage leaves in the jug. Leave the cabbage leaves in the boiling water to soak for a few minutes, until the water absorbs colour from the leaves. You can leave them in there for as long as you like, but the longer you leave it, the more concentrated the cabbage indicator solution will be – like brewing a teabag.

Step 3: Pour some of the cabbage indicator solution (the colourful water) into a cup or shot glass.

Step 4: Add a little of your chosen household product to the cabbage indicator solution in the cup or glass and look out for any colour change.

Step 5: Repeat steps 3 to 4 for a range of different household products. Try putting several glasses full of indicator side by side and add different products to each glass. You can even be quantitative: add a substance like lemon juice until you observe a colour change, and keep a note of how many drops (or what volume or weight) you added. Do the same for another substance like vinegar. You can then see which is more acidic (or basic), and even rank all your products on an acidity scale. Finally, you can neutralise your acids (so they behave like water) by adding bases to them, and vice versa.

Step 6: Wash your solutions down the sink and clean up the work space. Throw away the cabbage leaves.

Brief explanation

What you will have noticed from the experiment is that cabbage indicator takes on a range of different colours, depending on the household product added. The reason it’s called an indicator is because it indicates the acidity of the environment around it. Neutral substances like water will leave the indicator with its natural purple-blue colour that you see when you first boil the red cabbage leaves. Acidic substances like lemon juice cause the indicator to go pink or even red, while basic (alkaline) substances like ammonia will generate a green colour.

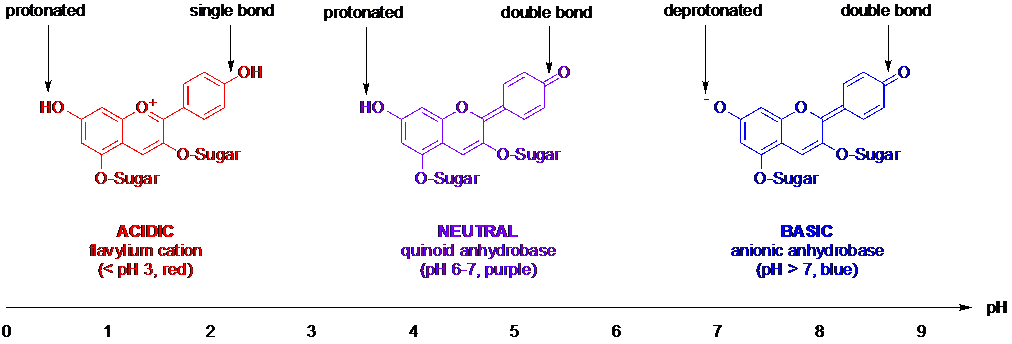

Cabbage indicator contains naturally occurring molecules made by the cabbage plant called anthocyanins. They have a complicated chemical structure based on rings of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen atoms. The anthocyanin molecule can rearrange its structure and bonding, and hence its colour, depending on the acidity or basicity of the surrounding solution.

These anthocyanin molecules found in red cabbage change their chemical bonding in response to the acidity (or basicity) that surrounds them, because acidic substances release protons (positively charged hydrogen ions, given the symbol H+) into the water in which they’re dissolved and create an excess of protons, whereas basic substances capture protons and create a proton deficit. The concentration of H+ ions is measured by the pH of a solution, where acids have a pH of less than 7, water is described as neutral, pH = 7, and bases have a pH larger than 7. In acidic conditions, the bonds in anthocyanins rearrange to accept H+ from the surrounding solution whereas in basic conditions, the bonds rearrange to release H+ to the surrounding solution to lower the deficit. These changes in bonding affect the structure of the anthocyanin molecules, and therefore the colour.

See the diagram below for simplified representations of the bonding patterns in anthocyanins at different pH values, with some of the key differences between the structures highlighted.

These changes in bonding are reversible, so you can keep adding acid to turn the indicator solution red and then adding base to return it to its purple state over and over again. When the acidity is somewhere in between very acidic and neutral (or between neutral and basic), some of the anthocyanin molecules will be in one state (such as red) and some will be in another state (such as purple) – the two states are in equilibrium. As a result, if you gradually change the solution from acidic to basic, you will see a smooth change in colour rather than a sudden, sharp change at a particular pH. In other words, the balance between the concentrations of the different colour states of anthocyanins (the equilibrium position) gradually shifts as the pH changes.

Find more details and a full procedure on the RSC Learn Chemistry website.